The use of embryos within modern medical research and treatment has created a flurry of ethical discussion.

There was a time when the intricacies of embryonic development were unknown to us. Pregnancy and childbirth were firmly within the 'mysteries' of nature and any discussion about beginning and ending early life centred around the ethics of sexual relationships (the context within which the life was created) and abortion (specific intervention to end that life). These issues are covered in great detail elsewhere.[1]

The advent of embryonic biology, and more recently reproductive technology has opened up a whole new arena. Where before there were many mistaken notions about early life [2] we now understand the processes of fertilisation, blastocyst development, implantation, differentiation and development. This may strip some of the 'mystery' away, but the intricacy of early life – and all that we still don't completely understand – still gives grounds for wonder and can give us a respect for very early life that perhaps didn't exist before.

This new knowledge also brings responsibility. Two broad movements have arisen from our progress in this area:

- Reproductive technologies – the creation of embryonic life outside the normal natural processes with the purpose of implantation and pregnancy (in vitro fertilisation etc).

- Utilisation of embryos – primarily embryonic stem cell (ESC) research, most frequently with the aim of developing stem cell treatments.

The first has been discussed in previous Nucleus articles [3] and has been generally accepted by society. The second still raises considerable controversy, with many vocalising opinions on either side of the debate. The ethics of utilising embryos for research can be divided into two sets of questions:

- Questions of philosophy and faith – broadly characterised by the 'personhood' debate, and the question of whether an embryo is a person.

- Questions of science and fact – the difficulties of biologically defining what is an 'embryo'. This is heightened by the development of new 'methods' for creating 'embryonic entities'.

This article will now turn to unpacking the second set of questions and to discuss how these 'facts' might be applied to our ethical thinking on embryo utilisation. In order to do this, I shall work from the initial basis of valuing the embryo as a person correspondent with an adult person and therefore an entity that is owed the same level of respect and protection as any other human being – the position that Peter Saunders argues for in his article in this issue.[4]

UK law and the 'embryo'

An embryo was defined in section 1 of the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act as: 'a live human embryo where fertilisation is complete, and references to an embryo include an egg in the process of fertilisation, and, for this purpose, fertilisation is not complete until the appearance of a two cell zygote.'[5]

The wording here is confusing and internally contradictory: an embryo is both 'complete' in the process of fertilisation and 'not complete' until that process is over. This confusion was highlighted by the 2000-02 'cloning loophole' court battle between the ProLife Alliance and the government.[6] The final outcome of that case, which went through to the House of Lords, was that the HFE Act extends to all human embryos created (by any means) outside the body. The 2001 Human Reproductive Cloning Act, which was rushed through by the government in response to 'panic' about reproductive cloning after the ProLife Alliance initially won at the High Court specifies that only a human embryo created by fertilisation can be placed in a woman. This division of types of embryos enables the government, via the HFEA, to permit the creation of embryos by cloning and various other means for research purposes only. It also means that certain embryos, whatever their capability for life may be, cannot legally be given a chance at developing further than the 14 day research limit imposed by the HFE Act. This sets the 'true' human embryo as one created the 'normal way' – through fertilisation of a human egg by a human sperm – though perhaps in vitro rather than in vivo.

Embryos for research

The normal source of embryos for research has been the unwanted and the unwell – ie. 'spare' healthy embryos from infertility treatment, or embryos of insufficient quality to be transferred to the womb. Proponents argue that these embryos will be destroyed anyway and therefore utilising them for research can bring good out of the situation. Just to dispose of them appears wasteful in comparison. Opponents are not armed with an alternative realistic prospect for the embryos. There is embryo 'adoption' (such as the US SnowFlake scheme [7]), but this is unlikely to cover the 100,000 or so spare embryos currently in storage in the UK. Also, embryos of low quality would not be suitable for adoption - they are highly unlikely to implant successfully and develop, while not many would actively seek – or perhaps even be allowed – to use one diagnosed by pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) as having a genetic disorder.

This lack of realistic alternative solutions highlights the current difficulty for opponents of embryo utilisation. Whilst not wanting embryos to be utilised in research, we are also faced with a glut of spare embryos that face destruction if not utilised. Ethically we are being faced with decisions that we can't find an acceptable solution to – the reality being that we would rather this situation had never been created in the first place. This is why many Christians using IVF may now opt for having only one or two embryos created at a time and then transferred – so that they don't end up with 'spare' embryos on ice that they actually don't want to have transferred and brought to term. Normal treatment would result in eight or so embryos being created. Our feeling that 'we'd rather you hadn't even created this embryo' applies also to many of the methods described below.

The need for 'non-embryo' embryos

Scientists wishing to pursue ESC research (and particularly cloned ESC research) have faced opposition from a variety of quarters. The force and effect of this opposition (teamed with the shortage of eggs donated for research) has prompted researchers to develop new methods of making 'embryonic entities', which differ biologically from the embryo as defined above. They are seen as 'non-embryos' in this respect and therefore argued to be ethical sources of ESCs – enabling scientists freely to pursue ESC research and therapy.

Yet many are not comforted by the creation of these other entities – they are still spoken of as embryos, and if not embryos, how are they useful for producing embryonic stem cells? In order to develop an ethical position on these entities, we first need to know the facts about what they actually are.

Embryonic entities and their uses

Parthenotes

Parthenogenesis: 'process in which an unfertilised egg develops into a new individual'[8]

Literally meaning 'virgin birth', parthenogenesis is a natural process that enables invertebrates and some plants to reproduce asexually. Mammals cannot naturally reproduce this way but scientists have found that a mammalian oocyte can be coaxed into re-recruiting its polar body (a 'sac' containing half the genetic material from the meiotic cell division that is part of gametogenesis) to become diploid again and continue with cell division as if fertilised.[9] The resulting parthenote will develop far enough to act as a source of ESCs, but is non-viable in the long-term as the duplication of maternal chromosomes is lethal.[10] For this reason, parthenotes are considered by some as an ethical source of stem cells on the basis that harvesting them for ESCs does not destroy a viable embryo.

In 2003 the Roslin Institute in Edinburgh was granted an HFEA licence to use parthenogenesis as a research tool.[11] They reported last year [12] that they had successfully created and developed six parthenotes to a stage where they could be 'mined for stem cells' – though they had not yet managed to obtain the hoped for ESCs. If successful they plan to generate ESC lines for research and development of new medicines. The stem cells will not, at this stage, be transplanted into human subjects.

Practical reservations about parthenotes can be raised, a number of which apply to other entities:

- Experimental parthenogenesis in mice, monkeys and humans is reported to have poor outcomes in both its efficiency and the quality of the parthenotes.

- It took the Roslin Institute approximately 300 eggs (donated by volunteers) to generate six parthenotes.

- There are significant scientific doubts about how useful parthenotes will prove to ESC research, partly because of the difficult manner of their creation, and also the fact that they are, by definition, not 'normal' embryos.

Researchers investigating parthenotes defend the work saying that all potential routes to obtaining clinically useful ESCs should be pursued. Additionally, the process may help answer remaining questions about embryonic development that could prove applicable in alternative research areas.

Human-animal hybrids

Hybrid: 'an offspring of two animals or plants of different races, breeds, varieties, species, or genera'[13]

In recent years scientists have created human-animal hybrid embryos by inserting human nuclei into non-human eggs using the cell nuclear transfer method developed for cloning. Using animal eggs is primarily an attempt to overcome the shortage of human eggs for research, with the expectation that the hybrids would be grown to blastocyst stage and then mined for stem cells. Additionally the inter-species combinations could be a useful research tool to investigate nuclear programming.

In 1999 Advanced Cell Technologies announced that they had inserted the nucleus of an adult human cell into an enucleated cow's egg. The hybrid developed for twelve days before being destroyed.[14] In 2003, USA based Panayiotis Zavos claimed to have similarly created 200 cow-human hybrids that lived for two weeks and appeared to have normal human DNA.[15] Also in 2003, a Chinese researcher announced the creation of rabbit-human hybrids that grew to about 100 cells.[16]

Embryonic chimeras [17,18,19]

Chimera: 'an organism consisting of two or more tissues of different genetic composition', 'a Greek mythological fire-breathing she-monster that was made up of grotesquely disparate parts (traditionally a lion, goat, and serpent).'[20]

One method of creating a chimeric embryo would be to inject human ESCs into an animal embryo. The resulting chimera could be transferred to an animal womb to develop, the aim of such research being to investigate the developmental processes of different cell populations, to extract cells for testing, or to grow the human cell populations into functional tissues and organs for tranplantation into a patient.

These entities raise concerns in relation to how much certain 'human' characteristics will be exhibited by the chimera. People have far greater concerns about the human cell population generating brain tissue in a chimera - potentially resulting in 'human consciousness' - than they would about, say, a human liver growing in an otherwise very piggish, pig. The idea of a humanised mouse, or the 'humanzee', raise a considerable 'yuk factor' response – perhaps signifying a valid moral repugnance, or alternatively fear of an unknown and unusual. As one commentator noted: '… why do so many people believe it is wrong to breach the species barrier? Does the repugnance reflect an understanding of an important natural law? Or is it just another cultural bias, like the once widespread rejection of interracial marriage?'[21] Placing the yuk reaction aside, a humanised mouse would raise considerable questions about the nature of humanity and how we should treat the chimeric entity.

An immediate objection to the technology (whatever kind of animal will result) lies prior to the creation of the chimera, as human embryos are destroyed to obtain the initial ESC population that is injected into the animal embryo.

Engineered to have a fault

A 2005 study reported successful derivation of ESCs from cloned mouse embryos that had been genetically altered so that they could not grow a placenta.[22,23] This process, labelled 'altered nuclear transfer' (ANT) is proposed as an ethical alternative to CNT because of the abnormality of the blastocysts. Being inherently unable to implant into the uterus means 1) that there is no risk of 'reproductive' cloning happening as a result of this method and 2) mining them for stem cells does not destroy an embryo capable of development. This is the hinge for their 'ethical acceptability' – that, being incapable of further development, it is not inappropriate to utilise them for research and potential life-changing treatment. In this, the method may be comparable with organ transplant – removing a 'living' organ from a just dead, or as-good-as-dead, cadaver to benefit a living human being. The big difference being, of course, that we have purposefully developed it with a fault – we are responsible for the fault. It seems an illogical extension to then say that – it being purposefully damaged by us, it is therefore ethical for us to utilise it, particularly since the damage was inflicted with the specific purpose of enabling utilisation.

John Wyatt's analogy of the 'flawed masterpiece'[24] may be useful in considering this and the other techniques described in this article: a great painting may 'get defaced, it may decay from old age, the varnish may be cracked and yellowed, the frame riddled with woodworm… But through the imperfections we can still perceive a masterpiece.' To stretch this analogy, if I walked into the National Gallery and threw a can of white gloss paint over Constable's The Hay Wain, and then tried to argue that they may as well let me take the painting now that it's damaged, I don't think they'd agree. They would rightly see my defacing the painting as the main problem.

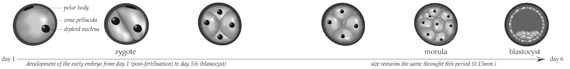

Removed from another embryo by biopsy

At the same time that the ANT method was published, another group announced their research into another alternative route to 'ethical' ESCs.[25,26] Advanced Cell Technology (Massachusetts) wrote that 'The most basic objection to ESC research is rooted in the fact that ESC derivation deprives embryos of any further potential to develop into a complete human being.' They have answered this objection by harvesting ESCs using a similar method to that used in PGD. Embryo biopsy, as far as we know, appears not to interfere with the further development of embryos.[27] Using this method they successfully grew mouse stem cell lines from a single cell taken at the eight cell stage. Stem cells are usually harvested from the inner cell mass (ICM) at the blastocyst stage. (See illustration below)

However, the ethical acceptability of this method would depend on a couple wanting to have the biopsied embryo transferred. A couple having IVF treatments would have to consent to their embryos being biopsied prior to transferral. Without any therapeutic benefit to the embryo (and added risks) it is hard to see how this will be acceptable to couples practically, or ethically justifiable under a risk/benefit analysis. However, it is also possible to see that if this were proven as a safe, effective route for gaining ESCs, some couples might want to engage with it in order to have a 'bank' of ESCs for their child's potential future needs.

An ethical framework?

From Peter Saunders' article in this issue, we may draw out the following reasons for the high moral status of normal human embryos. They are:

- biologically human

- new individual organisms

- part of a (potential) continuous process to birth and adulthood

- made in the 'image of God'

In this vein we might apply the following questions to the various embryonic-entities under discussion:

- Is it human?

- Could it be part of a continuous process that would result in a birth / adulthood?

- Is it made in the 'image of God'?

- What would God's justice require of us in our attitude and treatment towards this entity?

However, these questions become rather over-philosophical in the face of hybrids, chimeras and parthenotes. Is a hybrid human? If so, do you implant it into the human womb, or an animal one? How much human content must a chimera have to be human? Many of these entities cannot develop fully as far as we know – but how would we ever find out, other than by trying, and would we really want to try? Ultimately it is rather like being presented with Frankenstein's monster and being asked 'what now?' The answer is surely, 'you should have asked me before you made it!' It isn't possible for one who considers the previous steps unethical to develop an ethical framework for the current setting.

Additional arguments against these practices could centre around:

- The use of resources. How much energy and money is being poured into these developments? Couldn't these finite resources be better placed elsewhere?

- The alternatives. Adult stem cells and cord blood stem cells present an ethical resource, and in the case of cord blood, one that is largely unexplored and daily wasted (how many placentas are disposed of without the stem cells being harvested?).

- The many problematic issues about getting human eggs for research.

The allure of ESCs

The dogged insistence of the scientific establishment in the UK that ESCs must be researched – despite the concerns, alternatives, and many objections – must boil down to their pluripotency. As the embryo develops, the cells gradually become more differentiated. Cells from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst are capable of producing any cell, tissue or organ of the body if given the right conditions. And this is the last stage at which this is possible, as the first differentiation – into multipotent cells – happens as the embryo implants into the endometrial wall.

Differentiation continues, and humans are born with specialised cells organised into various components and with stem cells (both multipotent and unipotent) to replenish our bodies – but not with the life-generating 'everything' cells. 'Mining' the ICM for ESCs seems to me, ultimately, about cannibalising the life out of an embryo – when it is in its earliest, and thus most potent phase – in order to feed our lives. It is essentially a repackaging of the Darwinist ethic that the weak should be sacrificed for the strong. This is diametrically opposed to the Christian ethic of the strong laying down their lives for the weak.