At any one time, one in six people in the UK struggle with a mental health problem, and one in four will be unwell over the course of a year. (1) Overall, around one in three GP consultations involves mental health problems in some way. (2) Depression is the most common of these, with between 8% and 12% of the population meeting diagnostic criteria for depression in the course of a year. (3) Anxiety disorders are also common, and individuals regularly present with a mixture of low mood and anxiety.

These common mental health conditions have a significant impact on the lives of those who experience them. Whilst many manage to hold down jobs and maintain a high level of functioning, many others may experience difficulty in staying at work, maintaining relationships and in family life.

What is a depressive disorder?

All of us can feel sad or low in mood from time to time. Usually such changes are in response to external events, and low mood improves quickly. It is when symptoms worsen and last for a significant time that a diagnosis of a depressive disorder is made. The criteria for this diagnosis are outlined in Box 1.

Changes in thinking are common, with the person with depression adopting negative views of themselves, their situation and of the future – Beck's so-called negative cognitive triad. (5) Another distressing feature is hopelessness, which is the strongest predictor of suicide. Engagement in activity is often affected with reduced activity and increased avoidance.

Depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities for more than two weeks

Mood represents a change from the person's baseline

Impaired function: social, occupational, educational

Specific symptoms, at least five of these nine, present nearly every day:

1. Depressed mood or irritable most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (eg feels sad or empty) or observation made by others (eg appears tearful)

2. Decreased interest or pleasure in most activities, most of each day

3. Significant weight change (5%) or change in appetite

4. Change in sleep: Insomnia or hypersomnia

5. Change in activity: Psychomotor agitation or retardation

6. Fatigue or loss of energy

7. Guilt/worthlessness: Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

8. Concentration: diminished ability to think or concentrate, or more indecisiveness

9. Suicidality: Thoughts of death or suicide, or has suicide plan

The causes of depression

A range of factors can be involved in the aetiology of depression. Stressful life events (especially around bereavement, debt, relationship issues or unemployment) are a causal factor for some. Physical illness (such as ischaemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, thyroid problems, folic acid/vitamin B12 deficiency and cancer) may also lead to depression in others. Other background factors which may be related include a genetic predisposition, personality, upbringing and earlier life events, loneliness, lack of access to support, alcohol and drug, though this is far from an exhaustive list.

In reality, a combination of interacting factors tends to be involved, which can often be best combined in a psychological 'formulation'. This attempts to summarise the core problems, and brings together how they relate to each other. A formulation should also look at what factors have contributed to the problem in the first place, have kept symptoms going, and point to interventions based on this assessment. This approach allows a more nuanced and relevant understanding of a person's situation and difficulties than a single diagnostic statement would allow.

How do Christian faith and depression interact?

Christians are not immune from depression and anxiety. There are a number of interactions between the two, and many studies have investigated the extent to which religious belief correlates with various mental health problems. (6)

On the one hand, for those struggling with depression, faith can be a source of great support offering hope, comfort and purpose in suffering, social support and regular activity. Some may take comfort in God's promises from the Bible, and prayer may feel like a valued opportunity to communicate with someone who truly loves and understands them.

However, for others, there can be a perception within Christian settings that one should be always experiencing 'joy' and lives of 'victory', and this should present as unwavering happiness, or a need to present oneself as 'fine' and without problems. Indeed, to some people, in spite of the lessons of the Bible (eg the book of Job, many of the Psalms and the life of Jesus and the apostles), it may feel as though admitting that one is sad or scared may be seen as an indicator of weakness of faith, or a lack of prayer. Some may have been told this by Christians around them.

In such circumstances, faith can have a negative effect on depression, as not only are people experiencing depression, but they are also made to believe that their depression is in some sense their own fault, a weakness in their faith, or a result of specific sins in their life. Whilst specific sins may indeed be present and activities that are worsening the situation can be tackled, a key element in resolving the person's situation is an understanding of the abiding love and forgiveness of the God of grace. Sometimes false guilt can occur, where the person condemns themselves for small failures that do not reflect objectively present sin.

There may also be other specific parts of Christian life that are affected by depression, and cycles that Christians could find themselves in. For example, the person may lack the motivation or concentration to pray, or complete personal Bible study. Struggling with these things may lead a Christian to feel that he or she is failing in their faith or is not 'good enough' as a Christian, leading to a further reduction in their mood. A vicious circle is formed.

A Christian with depression may find there are specific hurdles associated with church attendance. Some typical examples might include a perceived expectation to chat to others after the service. They might wrongly anticipate the thoughts of others, with unhelpful predictions such as 'they'll know I've not been for a couple of weeks – they'll think I'm a bad Christian' or a 'catastrophising' thinking style with a thought like, 'I might start crying, and everyone will look at me and think I'm crazy'. Consequently, a Christian may avoid going to church altogether, thus forfeiting the potential social and spiritual support this could provide.

Christians may also think that their depression may require a different treatment approach than what someone who is not a Christian may require. Sometimes Christians believe that a secular health profession would not understand the specific challenges that a Christian might face, particularly when core symptoms may relate to feeling distant from God or unable to pray. Consequently, they may tend to seek Christian support for their depression rather than consulting a secular health professional. Many church leaders and members may be equipped to support someone with depression, but it is likely that the majority have not had specialist training in this area. Consequently, the depressed Christian may miss out on receiving an evidence-based intervention such as antidepressants or talking therapies that could benefit them. All accredited CBT practitioners should respect and work with the beliefs of their clients.

CBT is a primary treatment option

Whilst individuals may feel like there is no hope, some interventions have been shown to be effective for depression. Medication, most commonly Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), can be particularly effective for more severe episodes of depression, although the evidence base for milder depression is less clear. (7)

Over recent years, there has been an increasingly strong body of evidence for a range of psychological interventions to help treat depression, as well as a number of anxiety disorders. (8) (9) The most widely evaluated of these is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). CBT is most commonly conducted in weekly therapy sessions one-to- one over a period of weeks or months depending on the nature of the problem and proposed intervention.

The cognitive model of depression (10) is based on the rationale that an individual's mood and behaviour are determined by the way in which they interpret the world around them. Central to this is the understanding that it isn't events themselves that cause depression, but how a person interprets those events. Accordingly, the most effective means of intervening is to identify and challenge inaccurate thoughts that lead to unpleasant feelings and unhelpful behaviours.

CBT uses a structured approach, rather than simply providing space for the patient to talk about their problems at great length. It tends to focus on an individual's current experiences and difficulties, as well as how lessons from the past affect them today. A collaborative approach is adopted, where the therapist and patient work together as equals with different strengths. This is used to help the patient recognise connections between their thoughts, feelings and behaviours so they can work out together why they feel as they do. The therapy then moves on to teach specific strategies to help identify and change upsetting thinking, face fears, build confidence, and learn skills of problem solving that can be used in everyday life such as addressing an issue with a neighbour, or planning a response to a difficult colleague.

Does CBT work?

Many randomised controlled trials have shown CBT to be effective in reducing symptoms and improving quality of life across a range of conditions including depression. Consequently, NICE guidelines suggest that individuals experiencing depression should be offered CBT. (11)

Whilst the efficacy of CBT is clear, many people may face problems accessing CBT within the NHS. Given the large number of people who struggle with depression and anxiety, and the limited numbers of professionals equipped to provide such an intervention, there have been substantial discrepancies between levels of supply and demand. (12) This has sometimes meant long waiting lists for services, and reluctance among GPs to even make referrals for psychological interventions due to the long wait for a service. The recent development of shortened ways of delivering CBT, including the use of CBT books, classes and computer programmes has meant local mental health services have more ways of providing CBT to a greater number of people.

The CBT model in practice - a Five Areas approach

One criticism that can be made of the traditional CBT approach is that the language used tends to be complex, adopting terms that not immediately understood by practitioners or patients. The Five Areas approach (13) aims to provide a user-friendly and accessible form of CBT that can be easily understood.

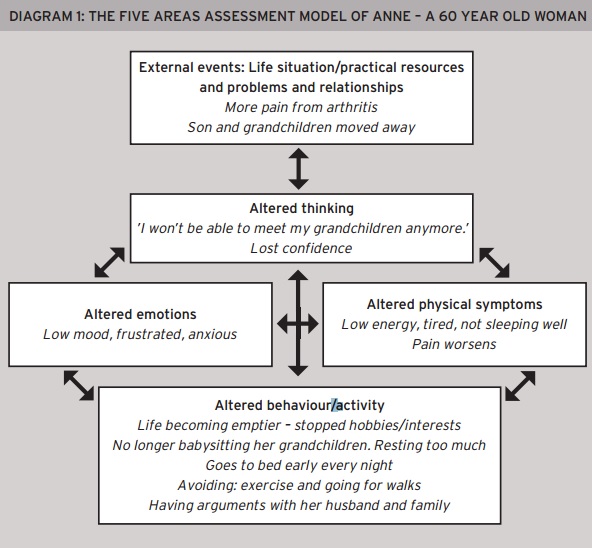

It offers a whole-person assessment that helps the person identify problems they face in each of five areas of their life:

- External events – the different life situations, relationships, practical resources and problems around the person.

- Altered thinking with extreme and unhelpful thoughts.

- Altered emotions – mood or feelings such as low or anxious mood, shame, guilt and anger.

- Altered physical feelings/symptoms in the body such as pain or low energy.

- Altered behaviour or activity levels such as avoidance and reduced activity.

An example of a completed Five Areas Assessment model is shown in Diagram 1 which summarises the case of a 60 year old woman who has felt anxious and depressed for the last six months. It shows that what a person thinks about a situation or problem may affect how they feel physically and emotionally, and also alters what they do (behaviour or activity). Each of these five areas affects each other.

The diagram shows that making changes in any of the areas can be helpful. Targets can be identified for change and intervention as well as providing a rationale for why Anne feels as she does. The model can summarise a range of situations and physical diseases in addition to mental health problems and can incorporate faith-based relationships and church and with God.

Making changes using CBT

CBT brings about change predominantly by focusing on addressing three of the five areas:

External events (Area 1) – a problem solving approach can be used to tackle external difficulties in relationships, or problems such as debt.

Altered thinking (Area 2) – for example, if someone is expecting to receive a phone call from a friend, and they do not call, they might think to themselves 'I must have upset them', which may lead them to feel sad or worried. An alternative, more helpful thought might be that 'my friend must have got held up at work', which would make them feel more relaxed or sympathetic towards their friend. CBT attempts to identify unhelpful and inaccurate thoughts and helps the person to generate more helpful alternatives, which may leave them feeling better. It also encourages the person to step back and choose not to get caught up in such unhelpful thoughts that worsen how they feel, or affect what they do.

Altered behaviour (Area 5) – here three vicious circles are commonly targeted. They are:

a) Reduced or avoided activity

In depression, the person often struggles to maintain their activity levels because of their symptoms. They often force themselves to complete things they feel they must/should/ought to do. However, things they would usually do for themselves such as hobbies and seeing friends are often reduced or stopped completely. The result is that the worse they feel, the less they do, and the less they do the worse they feel. A vicious circle is established and slowly the person finds their life is emptied of activities that give them a sense of pleasure, achievement and closeness. This can be reversed by planning to complete activities that give a sense of pleasure, achievement or closeness to others, and are important to the person. This behavioural activation approach can be just as effective as the full CBT package for some people. (14)

b) Unhelpful behaviours

Activities like drinking too much, smoking, overeating, misusing medication, pushing people away and taking risks are commonly seen in depression. Such activities can be particularly distressing for Christians who find themselves acting against their faith in some way. These activities worsen how the person feels, yet are usually done because they provide a short-term relief from symptoms. CBT treatment includes recording what is being done, and identifying factors leading to it. Treatment plans focus on a slow reduction of these behaviours, whilst filling the gap with more helpful ones. To this, for Christians, can be added prayer support from local church teams, friends and other church members.

c) Helpful activities

-

A range of simple activities can be helpful including:

- Self-care – eg having a haircut or a massage.

- Meeting friends helps the person feel closeness with others.

- Doing a Wow walk (15) – This involves walking with someone else and Wow-ing at the amazing world around. This provides closeness, activity and choosing to focus on the positives, and for Christians can lead to praising God.

- Exercise – This helps prevent physical de-conditioning and boosts mood.

- Eating sensibly – three regular meals a day, including breakfast.

- Using music to lift mood and also avoiding tracks that remind the person of sad or angry times. Praise songs and albums may be helpful for Christians.

Using CBT with individual Christians

CBT is an approach that is compatible with the Christian faith, and can be of benefit to many Christians with depression. Indeed, Christians are called to 'take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ' (2 Corinthians 10:5), and to put off our corrupted old self and to be made new in the attitude of our minds (Ephesians 4:22-23).

CBT can incorporate Christian activity in simple, specific ways. For example, a Christian with depression may find prayer a struggle. Rather than trying to get back immediately to praying like they did before they became depressed, which would have a high chance of ending in failure, a CBT approach would suggest starting with very short prayers, and building gradually up as they become able to manage more. A similar approach can be taken to reading the Bible. Similarly, if a Christian has stopped attending church in order to avoid having to have any awkward conversations afterwards, a start may be for them to attend church but arrive late and leave early, or to ask a trusted friend to meet them beforehand.

It is likely that a Christian could benefit more from CBT delivered by a highly-trained and skilled non-Christian psychological therapist than from a well-meaning, but untrained Christian, who is less experienced in the effects and realities of depression. However, many Christians may also prefer to receive support from a Christian professional, from within a Christian community or from someone with a Christian perspective. Consequently, there are important ways that the church can help, and also that CBT techniques can be augmented to incorporate a Christian worldview more explicitly.

Although the evidence base suggests that CBT is the most effective intervention for depression, many Christians have found Christian counselling to be of benefit too. This may be particularly the case when problems relate more specifically to faith issues, or where CBT's 'here and now' focus has not dealt with the important past issues. However, there can be a risk that an emphasis on personal testimony and allowing 'space to talk' may create more distress. The evidence suggests that CBT approaches should be offered as a first line of treatment. This can be accompanied by faith-based supports and ministry from ministry teams, church leaders or fellow Christians. Also, increasing numbers of Christian counsellors are trained in CBT approaches and may be able to draw from both. (16)

Resources are available that combine the CBT approach with an explicit Christian focus, (17) and can be used by Christians, whilst at the same time using an evidence-based approach. Commonly recommended free, secular online courses include Living Life to the Full and Moodgym. (18) A faith-based version of Living Life to the Full is also available. (19)

How churches can help

Churches can play an important role in supporting people with depression, both those who are Christians and those who are not. The church is often seen to have a role to welcome those in society who may feel unwelcome elsewhere, and those who are struggling. Indeed many ministers will know that a large amount of their time is taken up providing pastoral care. Many with and without church backgrounds may see the church as a place to go in times of difficulty. Consequently, it is important that church workers feel competent to provide appropriate support to those people themselves, or to know where that support can be found.

Some churches have recently begun running groups based on CBT principles to reach out into their local communities, as well as to support Christians struggling with common problems like low mood and anxiety. Living Life to the Full is also available as a series of eight weekly classes/seminars that can be delivered in churches or communities. 20 As well as teaching important CBT skills, this course includes additional notes for use in churches and allows fellowship between Christians with depression, and encourages them to engage with each other about the interaction of their faith and their low mood or anxiety, providing a potentially helpful social support, and knowledge that they are not alone in their experience. Church workers may benefit from seeking training in how to use a basic CBT approach in their pastoral work and regular training courses are available.

It can also be helpful for church leaders to give a clear message that depression and mental health are things that can be spoken about in church. This might mean talking about depression within sermons, pointing to examples of well-known Christians who faced it personally, or encouraging open discussion about the issue within the church community. Indeed, Paul did not shy away from speaking about the suffering he endured for the sake of the gospel, but that God, who can raise the dead, can deliver Christians from this despair (2 Corinthians 1:8-12). This may help to reduce the stigma surrounding the issue as well as providing guidance for those struggling with it. It may also help to make it clear that biblical joy is not about smiling all the time and never feeling low or anxious, but the opportunity to rejoice in the fact that any present sufferings do not compare with the future glory that will be revealed in us (Romans 8:18) and that nothing can separate us from the love of God (Romans 8:38).

Conclusion

Depression is a debilitating condition that affects millions of people in the UK every year. Christians are not immune from depression, and may find particular struggles associated between the interaction between their faith and their depression. Evidence-based interventions are available such as CBT, which can be beneficial to Christians and non-Christians alike. Although some Christians may feel they need specialist support, CBT is compatible with the Christian faith, and can easily be modified to appeal specifically to Christians. Future research could helpfully investigate the specific challenges and struggles of Christians with depression, and the efficacy of interventions that incorporate their faith. The church can also play an important role in both supporting people with depression, and reducing the stigma surrounding the condition within the Christian community.

Dr Chris Williams is Professor of Psychosocial Psychiatry at the University of Glasgow.

Dr Ben Wiffen is a Trainee Clinical Psychologist at the University of Glasgow.

Acknowledgements: CW is author of the Living Life to the Full books, website and classes. The term Five Areas is a registered trademark of Five Areas Resources Ltd and is used with permission.

Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version Anglicised Copyright © 1979, 1984, 2011 Biblica.

Used by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Publishers, an Hachette UK company. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of Biblica. UK trademark number 1448790.