Definition: Cynicism is 'believing that people are only interested in themselves and are not sincere'. (1) It's not the same as scepticism, which is 'doubting the truth or value of a belief'. (2) While scientists should question truth claims, cynics are pathologically mistrustful of people.

The medical professional can be deeply cynical. There is much truth in medical dramas such as MASH, Cardiac Arrest, The House of God, House and Scrubs that illustrate the archetype. Medical humour is littered with cynical slang, which may act as a coping mechanism to make light of harsh realities on the wards. Yet, it too easily degenerates into a dehumanising stance towards patients, and a distancing for our own survival and self-interest. Consider these terms used on the wards:

- the pumpkin test - to shine a torch in the patient's mouth and see the eyes light up (a sign of low IQ);

- the grape sign - grapes at a bedside, signifies that a patient has a supportive family and might be candidate for early discharge;

- buff and turf - to re-hash the patient's story to make it sound more plausible for transfer to another specialty;

- donormobile - a motorbike, as the mortality and age of riders make them good candidates for organ donation;

- GPO - Good for Parts Only;

- celestial transfer - a death;

- ash cash - the money a doctor makes from a cremation form.

Why does it matter?

Cynicism is relevant to healthcare for three reasons. First, it has a direct impact on our health. A prospective study (3) scored 97,000 women on their agreement with statements like 'it is safer to trust nobody', and 'I have often had to take orders from someone who did not know as much as I did'. Those who scored highest on cynical hostility had a significantly increased mortality. (4) Conversely, optimism (which is more or less the inverse (5) of cynicism) is protective, especially for cardiovascular health. (6)

Second, the therapeutic relationship must be an open and trusting one. A colleague was shaken when a patient's brother pulled out an iPhone to record his examination 'just in case anything goes wrong'. This does not encourage open and honest communication. There is currently an epidemic of mistrust and suspicion in both directions, which leads to defensive medicine and surging legal costs. (7) Whilst medical students may start out thinking the best of their patients, evidence suggests that many gradually pick up a cynical mindset and a derogatory sense of humour. It may start as a means of coping with stress, but is often judgmental towards self-inflicted conditions and corrosive to compassion. (8)

Further, it's also an issue for organisations delivering care. With massive challenges for recruitment and retention, the NHS is under unprecedented strain. Leadership styles perceived as Machiavellian (selfinterested, manipulative and 'endorsing an untrustworthy view of human nature') cause organisational cynicism - 'a negative attitude toward one's employing organisation resulting from the perception that it lacks integrity'. Both factors lead to poor job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion and high staff turnover. (9)

Healthcare workers are particularly wary of managers. Authorities more generally are becoming less trusted and face increasing hostility: MPs' expenses, accusations of police racism, and the church covering up child abuse. Even hospitals are targets for cyberattacks and extortion. (10) But what management strategies make healthcare workers cynical? Doctors are encouraged to operate in a no blame culture and learn from their mistakes, but then find a confidential appraisal being used against them in court. (11) Yet, if they 'whistle blow' to raise concerns about safety, they are gagged, bullied or fired. (12) Health ministers have not been above suspicion. The BMA found one to have misused statistics for political purposes. (13) Another severely criticised doctors working in the private sector on the side, but then resigned his cabinet post to profit from contracts made in government in a private consultancy alongside his job as an MP. (14) Such double standards are like petrol on the fire of cynicism.

Behind the flippancy of the hard-bitten cynic is often a history of disillusionment. Cynicism serves as form of self-protection, an inoculation against future disappointment. If you trust no one, no one can let you down. To quote Dr Cox of Scrubs: 'That is why we distance ourselves, that's why we make jokes. We don't do it because it's fun - we do it so we can get by'. (15) Similarly, The House of God, the memoir that became a textbook of cynical humour, says that every doctor has this option: 'withdraw into cynicism and find another specialty or profession; or keep on in internal medicine, becoming a Jo, then a Fish, then a Pinkus, then a Putzel, then a Leggo, each more repressed, shallow, and sadistic than the one below... Could any of us have endured the year in the House of God and somehow, intact, have become that rarity: a human-being doctor?' (16)

A brief history of cynicism

Though we live in a particularly cynical age, it's not a new concept. Cynicism was given intellectual respectability, particularly as an assault on faith, over a century ago by Marx and Freud, the modern 'masters of suspicion'. They questioned the motivation behind faith rather than the factual basis of religion. Marx encouraged the suspicion that religion (particularly Christianity) was attractive because of its economic and social incentives, as it legitimised the status quo of 'The rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate'. (17) The poor must accept their station, sedated by the 'opiate of the masses', and await compensation in the afterlife for their sacrifices. Meanwhile, because their privilege is God-given, the rich can use religion as a smokescreen to justify selfishness and maintain their status. Similarly, Freud claimed to 'see through' faith and saw God as a crutch for our fears and inadequacies. Just as childhood feelings of helplessness are eased by belief in their parents' competence, so deep down belief in God is wish fulfilment, particularly in the face of death. A Father in Heaven is an infantile projection that offers consolation for the weak. It's interesting that the father of psychotherapy pioneered shame as an academic weapon to embarrass his adversaries into submission, rather than debate whether such beliefs are warranted. It was a cynical move and has been widely used since.

But cynicism is older still. The word 'cynic' is often ascribed to Diogenes (412-323 BC), a Greek philosopher, because of his canine lifestyle: the Greek words Kynikós means doglike. He lived on the street like a dog and slept in a barrel. Diogenes acted out his suspicion that man is nothing more than an animal in humorous ways. Once he took a lamp in broad daylight through the streets pretending to look in vain for an honest man. Today this has become standard teaching at university: evolutionary psychology reduces all human behaviour to self-interest or the selfish genes that have shaped us. We're all dogs in a dog-eat-dog world - altruism, love and God are all delusions.

Biblical perspective

1. Cynicism is older than humanity itself

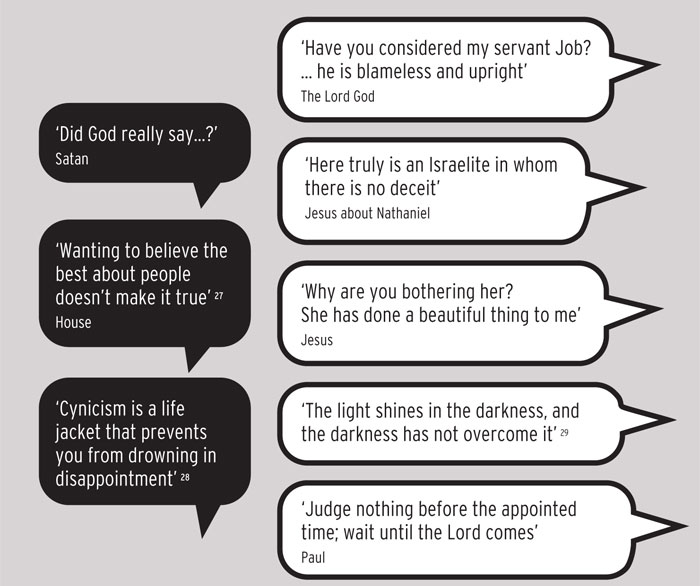

What is the Christian perspective? Though the word 'cynicism' does not appear in the Bible, it does warns scoffers that mocking all apparent virtue is self-defeating, a cause of spiritual immaturity and regret. (18) But it is a danger for mainstream people of faith too, as even the psalmist was tempted by negative generalisations. (19) However, the story of suspicion and mistrust goes back further still. The archetypal cynic in the Bible is Satan, whose name literally means 'the accuser'. Satan's core message is that trust or faith is always a bad idea.

In Genesis 3, God had trusted Adam and Eve with stewardship of Eden. But Satan's purpose was to sow the seeds of suspicion by questioning God's character: 'did God really say...?' Here cynicism dismantled trust between God and his people. Sadly this ploy is as effective now as it was then. We exaggerate or distort God's prohibitions: Eve doubted God's goodness when she suggested that even touching the fruit would be fatal. Satan then accused God of malign motives behind his commandments - eating the fruit would open their eyes so that they would see through God's pretence of goodness. They didn't trust God to provide for them, so they snatched what was 'rightfully' theirs. The blame game immediately followed and continues to this day. A few verses after Adam sang a love poem to the 'flesh of his flesh', he could not even name 'the woman you [God] put here with me'. Adam blames Eve and Eve blames the serpent. Mistrust prevailed, and the world darkened.

When Satan appears in the book of Job, he reiterates that there is nothing but self-interest in the world - apparent goodness and faith is always instrumental, just a means to an end. God rejects this claim, he challenges Satan to 'consider his servant' Job. God knew that Job's faith was not merely self-interest, and he was proved right when Job demonstrated his integrity through various trials. So unexpectedly, at these key meetings with the arch cynic, the God of the Bible shows more willingness to be generous to the possibility of goodness than do his creatures.

2. Cynics are partly right

That said, the Bible does encourage us to be suspicious of fake virtue and deception, which is what cynics are so wary of. The Bible has plenty of biting satire, irony and even sarcasm to make this point. (20) The prophets warn us to 'beware of' self-serving rhetoric. (21) Cynics are right to expose it. Jesus did not make naivety a virtue. He 'knew the hearts of men' (22) and warned: 'I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves'. (23) However, cynics take this too far by assuming that everyone is a 'wolf', and that they know the motives in people's hearts and minds.

3. But cynics do not have the God's eye view: there is more good in the world than they recognise

For instance, it's one thing to notice that a politician once tried to claim a duck house on expenses. (24) It's another thing to say that all politicians only ever act in their own interests, that 'they are all the same'. To verify this one would have to read the mind of every politician who ever lived. But if Jesus was divine, he was uniquely qualified to give us the 'God's eye view' on this question. Was he ever cynical? Let's look at his response to blatantly self-serving behaviour in the closing hours of his life, in Mark 14:1-10:

Now the Passover and the Festival of Unleavened Bread were only two days away, and the chief priests and the teachers of the law were scheming to arrest Jesus secretly and kill him. 'But not during the festival,' they said, 'or the people may riot.'

While he was in Bethany, reclining at the table in the home of Simon the Leper, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, made of pure nard. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head.

Some of those present were saying indignantly to one another, 'Why this waste of perfume? It could have been sold for more than a year's wages and the money given to the poor'. And they rebuked her harshly.

'Leave her alone,' said Jesus. 'Why are you bothering her? She has done a beautiful thing to me. The poor you will always have with you, and you can help them any time you want. But you will not always have me. She did what she could. She poured perfume on my body beforehand to prepare for my burial. Truly I tell you, wherever the gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her.'

Then Judas Iscariot, one of the Twelve, went to the chief priests to betray Jesus to them.

Here is a party right before Jesus' death (25) where all kinds of dark motives are exposed: envy, gossip, greed, the threat of mob violence, back room politics, a secret defection, blood money and a murder pact. A gate crasher enters, who scandalises the onlookers by lavishing expensive perfume on Jesus. Questions about her motive followed: was it attention seeking, or perhaps a sexual motive? Judas objects and the disciples squabble about his motives. (26)

It's an ugly scene of accusation and counter accusation. The cynic might 'see through' each character, concluding that self-interest explains every behaviour. It's ugly and it stinks! But what is Jesus' assessment? He sees beauty. He smells fragrance: 'leave her alone, why are you bothering her...she has done a beautiful thing to me'.

Jesus did not 'see through' people or reduce them to their worst aspects. As CS Lewis wrote: 'You cannot go on "seeing through" things for ever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. It is good that the window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond it is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too? A wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To "see through" all things is the same as not to see'. (30)

It's remarkable that just a few hours before his death, Jesus did not despair at the profound selfishness around him. Instead he paused with a woman written off by her peers to celebrate genuine goodness. Elsewhere, Jesus said of Nathaniel 'Here truly is an Israelite in whom there is no deceit'. (31) Real faith, goodness and integrity have been rubber stamped by God himself. He never gave in to cynical despair.

Biblical treatment for cynics

Humility: people may surprise us

A common temptation for cynics is to adopt a critical, if not self-righteous, attitude towards others. But Jesus advised us to first search our own hearts. In a famous parable about a blind ophthalmologist, he warned 'How can you say to your brother, "Let me take the speck out of your eye," when all the time there is a plank in your own eye?' (32)We can barely fathom our own hearts, let alone someone else's: 'The heart is deceitful above all things and beyond cure. Who can understand it?' (33) We should be quicker to judge ourselves before others. Research bears this out. In a large international survey, people ascribed more undesirable behaviours to their neighbours than they were prepared to own up to themselves. For instance, they believed that 36% of the population avoided paying the right amount of tax, but only 6% admitted it themselves. We have a bias not to see the good in others and the bad in ourselves. (34)

When we are tempted to be cynical and think badly of others, we should remember that we can't read people's hearts any more than they can read our own. Paul was slandered, misrepresented and physically abused; he had reason to be suspicious of others. (35) Yet he had humility and grace. He recognised that there will be surprises on judgment day. So he advised patience: 'It is the Lord who judges me. Therefore judge nothing before the appointed time; wait until the Lord comes. He will bring to light what is hidden in darkness and will expose the motives of the heart. At that time each will receive their praise from God'. (36)

Faith

'And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.' (38)

A manager surprises a cynic

An unknown elderly man is brought by air ambulance to A&E following trauma, but after three cardiac arrests he is clearly dying, and his team are desperate to help him find a quiet space in which to die with dignity:

'The SHO tried to find a side room in A&E, he was told there are none to spare. "Best try get him to the acute medical ward", we were told. So he phoned the flow manager and begged for an urgent side room. Against the odds, they had one. My heart lifted. But they would not be able to take him "just yet". My heart sank.

"Typical management", I grumbled, and I sat and watched my patient, still hoping we could get him somewhere else before he died. Typical management.

After a very short time the flow manager arrived into resus. She was a nurse. She hurried to the bed and said she was sorry about the delay, that she had wanted to make sure she'd found a member of staff to be with the patient while he died.

She had brought a healthcare attendant and a bed and she asked if I would wait to extubate him until he was cleaned up and off the hard trolley. Then she took him to his room, left her phone there playing Mozart, and left him a hand to hold. Typical management.' (37)

Many cynics appear to be former idealists, whose life experience has made them lose faith in human nature. They have swung from an overly optimistic worldview (man is essentially good given the right conditions, a view held by secular humanism) to an overly pessimistic one (people are all the same - selfcentred and everything else is pretence). But what they need is a more robust anthropology (understanding of the human condition). The biblical view is honest about the corruption, but not despairing. It does not under or overstate the brokenness, and is hopeful about the possibility of change. Nothing can entirely eradicate the 'image of God', (39) however compromised. We are flawed masterpieces, glorious ruins, battered, marred, crumbling - but not beyond repair. Christ gives us confidence that God has not given up on humanity. So we needn't despair because we have reason to trust him.

Hope

Cynics often say that time is on their side: 'If you're not a socialist in your 20s you've got no heart. If you're not a capitalist in your 30s you've got no brain'. A cynic might say that the only thing that separates an optimist from a cynic is time and experience, that he's just a realist. But the slide into despair is not inevitable. Cynics are not the world-weary realists; they are just tired of the life-sapping effect of mistrust and suspicion. But, according to Jesus, light is stronger than darkness (40) and a new world order is coming where the current rules do not apply. The dog-eat-dog world order of the cynic is passing: there will be transformed relationships of trust and co-operation. This is poetically represented in the book of Isaiah by animals that currently tear each other apart: 'The cow will feed with the bear, their young will lie down together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox'. (41) This may sound otherworldly, yet the Christian hope is anchored, not in wishful thinking, but in the character and purposes of God displayed in history.

Love

But what about now? How can we learn to trust if we have been become suspicious and guarded? The woman who poured perfume on Jesus is a great example. She had every reason to be wary of the patriarchal party crowd who were hostile towards her. The cynics were wrong: she wasn't trying to manipulate Jesus' affections, she was already confident of them. He had proven his trustworthiness to her, so she was able to return his love generously, openheartedly and without fear. His affirmation gave her resilience to face a challenging crowd. If it's the same woman as in Mark 14, she loved deeply because she had been forgiven greatly. Isn't that a more desirable way to live than the self-protection and suspicious hostility of the cynics?

And what about the darker recesses of the NHS? Is it possible to change a culture infected by cynical attitudes? I once had a colleague who had a gentle and humorous way of challenging negative generalisations made behind someone's back: 'but they always speak so highly of you!' Perhaps small gestures of generosity, celebrating good in unexpected places can make a difference. Paul talked about Christians being the 'aroma of Christ… an aroma that brings life'. (42) Even a hint of fragrance can go a long way.

Reflection questions

- When have you been cynical about a colleague? A patient?

- What language perpetuates cynicism in your workplace?

- Do you think that distrust and suspicion function as self-protection?

- Can you think of occasions when you have been pleasantly surprised about someone's motives?

- What did Jesus do that might be an example for you?

Conclusion

Cynicism has a long history. It is the mistrust caused by disillusionment with the self-serving bias of human nature and sham virtue. It may be understandable as a defence mechanism, but cynicism is bad for our health, our relationships and the NHS.

Jesus did not advocate naivety, but modelled shrewd discernment of others. He challenged the cynical worldview that humanity is only ever self-interested or beyond redemption, and never became cynical himself. We need humility to recognise our part in the brokenness of the world. But we needn't despair: Jesus, through his death and resurrection, has given us good reason to trust (have faith) that change is possible. Therefore we can live in the hope of the future world order and not the shadow of past disappointments and have our hearts softened to be more generous, patient and loving towards others, as he was.

Further reading and listening

- Keyes D. Seeing Through Cynicism: A Reconsideration of the Power of Suspicion. IVP, 2006

- Meynell M. A Wilderness Of Mirrors, Trusting Again In A Cynical World. Zondervan, 2015

- Cynicism and hope. L'Abri Ideas Library.

Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version Anglicised. Copyright © 1979, 1984, 2011 Biblica. Used by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Publishers, an Hachette UK company. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of Biblica. UK trademark number 1448790.