It is more than six years since the Lancet published Dr Wakefield's paper describing a new syndrome of bowel disease and autism in MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccinated children.[1] Almost none of the subsequent research has found any evidence to support this causal link. Yet the controversy rages on. Rather than living with the theoretical risk of autism, many parents are facing the known risks of measles, mumps and rubella, or are paying for multiple, single immunisations.

At times the Government's continuing reassurance has strengthened its opponents' armoury.[2] After all, Dr Wakefield is a dedicated doctor (through neither a paediatrician nor epidemiologist), a father himself, whose painstaking work suggested the unthinkable: that a routine vaccine might be partly responsible for the surge in autism diagnoses over the past two decades. When he refused to end his research, his consultant position at a London teaching hospital became untenable. Eventually, with his supporters claiming persecution in Britain, he moved his research to the United States.

Some argue that general practitioners advocating MMR are not objective as the uptake proportions affect their practice incomes. Yet doctors who have seized the opportunity to set up single vaccine clinics have hardly brought honour to themselves but have cashed in on the fears of the lay public.

Systematic reviews

Meanwhile the evidence against a link between MMR and autism continues to grow. Recent systematic reviews of over 20 previous studies have failed to find any evidence of a link. This presents a dilemma for the media, which tends to present both sides of an argument, even when one side is a minority, maverick viewpoint.[3] Imbibing the media's reports, a confused public now feel that evidence in favour of a link between MMR and autism is finely balanced. Yet the idea behind systematic reviews is familiar to us all. Before buying a new car, many of us read every car magazine we can get hold of. If most reporters give it a glowing report, we ignore the one who gave it the thumbs down and follow majority opinion. So why do we act so differently over the immunisation of our children?

Legal action

Recently, the Legal Services Commission withdrew support for a class action involving the families of over 1,000 autistic children who sought compensation from MMR's manufacturers. £15 million of legal aid – £15,000 per child – had already been spent unsuccessfully attempting to demonstrate a link between MMR and autism. This compares starkly with £3.5 million committed by the Government in 2002 to the Medical Research Council's autism research programme. In pursuit of compensation, a number of these autistic children underwent colonoscopy and lumbar puncture. As no British hospital would perform them, seven children were flown to the United States for these tests. The results were unvalidated and uninterpretable.[4]

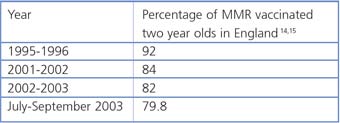

Immunisation levels

[14,15]

An immunisation rate of 95% is needed to confer herd immunity. In 2000, a Dublin measles outbreak of 355 cases resulted in three deaths. The MMR uptake rate in the affected area was only 70%.[16] Experts predict similar outbreaks here.[17] South East London had the lowest uptake in 2002-2003: only 66% of two year olds were immunised. The risks for measles encephalitis and death are around one in 1,000.[18]

Conflict of interest

Recently it emerged that some of the children in Dr Wakefield's study had been referred and funded through legal aid, despite no acknowledgement of this in his 1998 paper. Subsequently, Dr Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet, announced he would not have published the paper if he had known of this conflict of interest.[5] Since then, ten of Dr Wakefield's co-authors have issued a joint public statement, retracting the interpretation placed upon their findings.[6]

Disturbing questions

This debacle raises many disturbing questions about the nature of scientific research and the conveyance of its findings. It highlights the importance of high research standards. It was entirely reasonable to raise concerns about MMR's safety if research suggested harmful effects. However, prior discussion with other experts would have ensured that appropriate methodologies were followed. Editors of prestigious medical journals carry much responsibility. Had the original paper been published in an obscure paediatrics journal, subsequent medical history might have been entirely different. Vaccine opponents often take the line we should avoid MMR until scientists can prove beyond doubt that it does not, under any circumstances, cause autism. Yet science cannot prove a negative.

Are courts ever an appropriate place to prove or disprove medical beliefs? Indeed, had the MMR case proceeded to court, it would have made a disturbing precedent for future groups seeking legal aid to fund research for speculative claims. Is funding from any other source less controversial? After all, MMR's manufacturers and the Government sponsored Medical Research Council funded several of the studies that failed to find a link between autism and MMR. Opponents of the vaccine criticised these studies for potential conflict of interest whilst failing to admit their own. In the present climate, could any study be funded and conducted without attracting criticism from the 'other side'?

What happened when?

1988 MMR vaccination of children under two is introduced in UK.

1998 The Lancet publishes Dr Andrew Wakefield's study.[19]

2000-2002 Dr Wakefield's group describes a new variant of autism associated with inflammatory bowel disease and the presence of measles virus in the gut.[20,21] Other investigations do not support this.[22] Evidence suggests that the increasing prevalence of autism is linked with broader diagnostic criteria and greater awareness.[23,24,25]

2003 Epidemiological reviews fail to identify a causal link between MMR and autism. [26,27,28,29]

2004 The Sunday Times highlights a conflict of interest in Dr Wakefield's work.[30] A paper demonstrates no relation between autism and MMR, even in children with developmental regression or plateau, the subgroup covered by Dr Wakefield's 1998 study.[31]

Learning points

What can Christians learn from this unhappy saga? Firstly, we should not be afraid to pursue research but must do so in a responsible manner. We must recognise the limits of our abilities and not be afraid to seek advice from others.[7] Secondly, we should be aware of any conflict of interest, particularly financial.[8] Thirdly, we must elicit the trust of our patients and the wider public. Patients who supported Dr Wakefield commented that they trusted his team because they were really listened to.[9] Sadly, previous doctors had failed to inspire such confidence! Finally, it brings us back to the profound question that Pontius Pilate asked Jesus. What is truth?[10] Is it a commodity that can be bought with enough research resources or eloquent legal arguments? How do we convey truth when we believe we have it?

Christianity is an evidence-based faith. Events narrated in the Bible were diligently recorded to preserve what eyewitnesses saw as the truth.[11] Yet knowing the truth is not sufficient preparation for sharing it. Experts who are called upon to defend MMR's safety believe passionately in it. Yet, simply 'knowing the truth of MMR' and conveying this to the media has not been enough to persuade the public. Rather than merely confronting patients with hard medical facts, it is important to listen to their fears, build up trust and lead by example. 'Yes, I thought about it too but chose to protect my children with MMR.' Similarly, whilst we can be confident about the truth of the Bible, simply passing on these truths to sceptics is akin to tossing pearls before swine.[12] We should always be prepared to give an answer to those who ask us but in gentleness and with respect.[13]